The Panic Cycle

by Peter Walker

The Panic Cycle: The cognitive model of panic.

Panic attacks consist of an escalating feeling of terror and dread that is associated with a range of physical sensations. They are usually brief, in most case lasting for between 10 and 20 minutes. In some cases individuals report much longer panic attacks. The physical sensations are those that have already been outlined in the material on the “defensive cascade” or “fight or flight” response. Panic attacks can be associated with threatening situations such as public speaking, when confronted by some specific fear such as a spider or worrying about the future. In fact, the author writing this has experienced two panic attacks, one while he was sky-diving and the second when he was called into the hospital urgently as his wife was giving birth.

They can also occur “out of the blue” without a clear trigger or nocturnally (waking from sleep and having a panic attack). This can be very puzzling for the individual experiencing the panic attack and it can contribute to the belief that the panic attack represents a serious and potentially life-threatening physical problem. Unfortunately, as you will discover as you read on, these types of beliefs tend to maintain panic attacks unnecessarily. An explanation for panic attacks is therefore necessary. Further, the evidence-based treatment that is recommended for the treatment of recurrent panic attacks flows from the explanatory model.

Panic disorder is an anxiety disorder that affects approximately 1 to 2 % of adult Australians each year. The technical criteria contained within the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM- IV) requires “unexpected, recurrent panic attacks, followed in at least one instance by at least a month of a significant and related behavior change, a persistent concern of more attacks, or a worry about the attack's consequences.” (ref). The condition is often associated with a related condition called agoraphobia, which is an ongoing fear and avoidance of situations (public transport, tunnels, lifts, bridges, open spaces, shopping centres etc) that the individual believes may lead to panic attacks. It can be debilitating and in severe cases can leave people housebound.

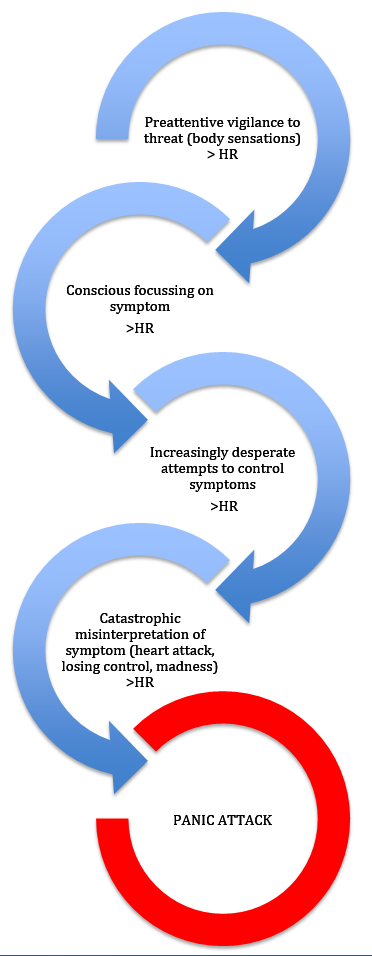

The figure below describes a number of stages that individual’s move through as they are developing a panic attack and is based on David Clark’s cognitive model, originally published in 1986. The first component of the model “Pre-attentive vigilance to body sensations”, in large part explains why panic can often occur “out of the blue”. There is substantial evidence that individuals who experience panic attacks (and anxiety in general) demonstrate an unconscious bias for threatening information. What this means is that, without being aware of it, our senses are processing the environment for danger. There is also evidence that in panic disorder specifically individuals demonstrate a hyper-vigilance to body sensations. This is pronounced in those with a history of panic attacks (Schmidt, Lerew and Trakowski, 1997). So what appears to be happening is that our brain is processing the world for danger without our conscious awareness. If someone has experienced a panic attack previously, their brain is most likely keeping a close eye on bodily sensations. As you’d be aware if you’ve ever had your blood pressure or heart rate monitored continuously for a period, our physical system is constantly moving. It may be that a minor, benign change in our arousal is then detected by our sensitive monitoring system. Hence “a false alarm” occurs.

The second component of the model refers to a “focussing” process. Once our brain has unconsciously detected a possible perturbation in our body sensations, it comes to our conscious attention and we focus on it. The process of focussing on anything tends to increase our arousal, further escalating our physiological response.

The third stage refers (perhaps a bit dramatically) to Increasingly desperate attempts to control symptoms. The subjective experience of a panic attack is aversive. Although not technically harmful, panic attacks are unpleasant. As a result of this individual’s understandably begin to do their best to get control of the process. Unfortunately, the techniques that people most often use tend to either lead to further escalation, or act to maintain the problems in the longer term. So, for example, most people have seen panic attacks characterised in popular culture and note that breathing into a bag is recommended. Further, it can sometimes feel as though you are out of breath when having a panic attack, so people commonly take rapid breaths typically from their chest (as opposed to diaphragmatically) and this inadvertently leads to hyperventilation, further increasing the fight or flight response. The other behaviours that people engage in that tend to maintain panic attacks in the longer term will be addressed later.

Finally, and importantly, panic appears to be driven and maintained by a tendency to misinterpret the symptom “catastrophically”. People worry that the symptoms they are experiencing represent a cardiovascular event such as heart attack or stroke, they worry they may be going crazy or that they are losing control of themselves and the consequences will be terrible. This understandably increases the very symptoms that are feared and resisted and often culminates in a panic attack.

These experiences can cause great functional impairments in individuals. The experience of panic can impair performance during complex tasks such as speeches. But perhaps the greater problem occurs when people avoid situations in which they fear they may panic. For example, people may start avoiding lifts because they worry that will panic and this context offers no possibility of escape or risks humiliation. This may then generalise to tunnels and planes and before you know it the person’s world has become very small. This is referred to as Agoraphobia.

Another complication in panic disorder are safety behaviours. They are a set of behaviours that someone with panic attacks engages in in order to feel safe. For example, some people will carry benzodiazepines such as Valium. They may never take them, but have them there “just in case”. They may then be more susceptible to panic attacks if they accidentally forget to take their pills. Other examples include carrying water, having high frequency appointments with their GP or keeping a trusted individual close-by. These behaviours make someone more brittle and tend to maintain panic.

Psychological Treatments

There are various treatment models for managing panic disorder, however, most treatments will consist of the following components;

Psychoeducation- The client will be provided with education about panic disorder.

Panic surfing- They will then be taught a method for managing panic more effectively when it arises. One such method is called “panic surfing” and was developed by Andrew Baillie and Ron Rapee (1998). This approach encourages clients to “go with” the experience of panic rather than resisting it.

Exposure- In-vivo- The client will then build a list of those situations that are being avoided and they will progressively return to them for extended periods of time. This acts to desensitise the individual and is a very effective, if distressing, treatment.

Interoceptive- The client will be intentionally exposed to symptoms that mimic panic attacks, such as hyperventilation or spinning on a chair. Again, the idea is to desensitise the person by encouraging them to face the thing they fear, the fight or flight response.

Cognitive Therapy- The catastrophic misinterpretations of the symptoms of panic will be assessed and challenged in light of evidence.